263. What I Learned from the Astronauts - Oliver Jeffers

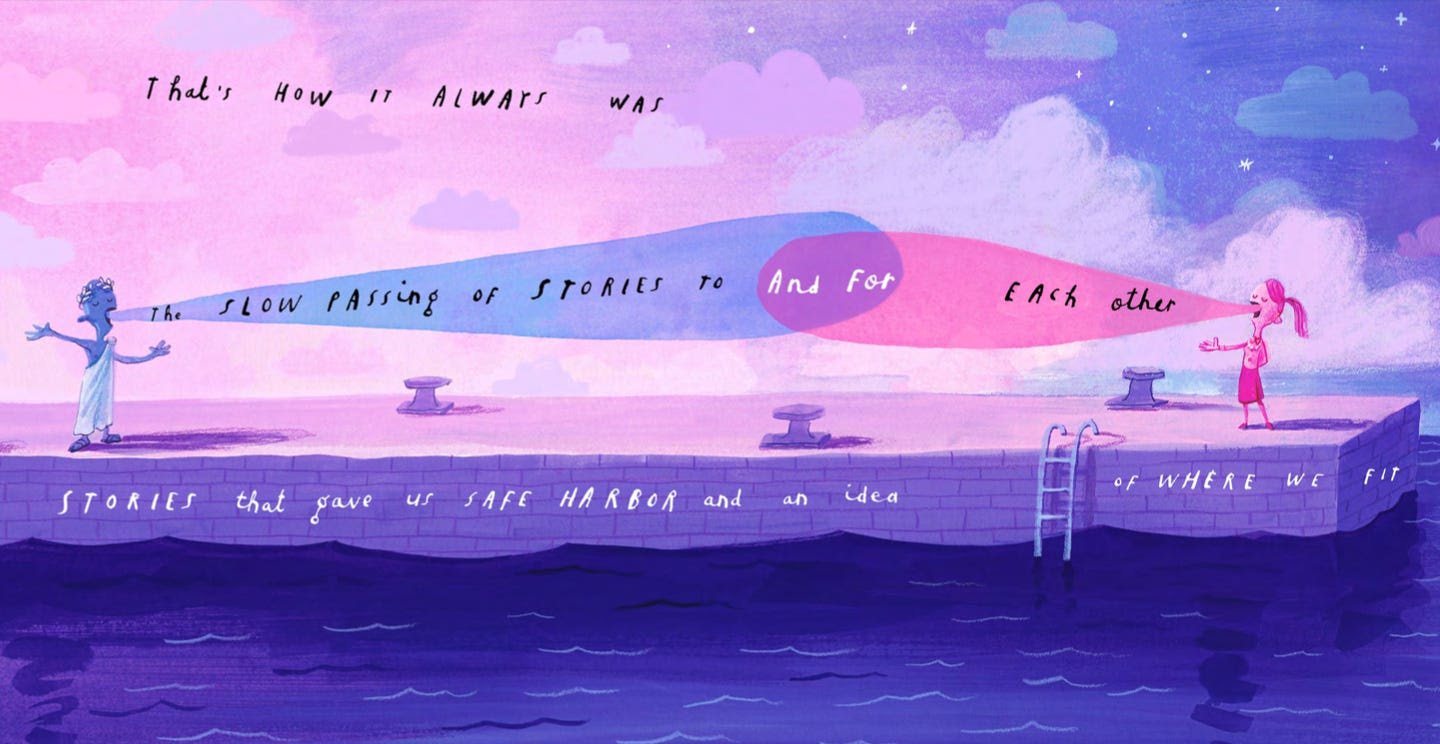

Illustration by Oliver Jeffers, from Begin Again

There is a phenomenon known as the overview effect, where any human who has been far enough from the surface of our Earth tends to have the same shift in perception.

There is a phenomenon known as the overview effect, where any human who has been far enough from the surface of our Earth tends to have the same shift in perception. In the first days onboard the International Space Station, astronauts take to pointing out their hometowns and cities, which shifts outward to their countries, then the rough continents that represent “home.” Finally a dawning realization plants itself firmly in their minds: this one object, floating in the cathedral of space, is home.

I grew up in the politically divided and violent city of Belfast, Northern Ireland. I know all too well the destructive patterns of an “us” and “them” mentality—how two opposing communities become insular and defensive, how their own identities become dependent on the existence of an enemy. “I don’t know who I am, but I know who I’m not” all too often spills into violence.

Raised as a Northern Irish Catholic, I am somewhere in the middle of that turbulence of fortune. I’ve experienced much of the grace and advantage that comes from being born into the body I inhabit. But I also come from a British colony—indeed the original British colony. For the best part of the twentieth century, Northern Irish Catholics were treated as second-class citizens in their own homeland.

But by the mid-1980s, the origin of all this conflict was lost on me. It had always seemed obvious that it was never a religious war, and by the mid-90s, it wasn’t clear that it had come from a class struggle either. Partly because I’d been told some of the stories, partly because I hadn’t been told others, and partly because I’d compared these stories with others far and wide, it seemed more like political terrorism on two fronts than anything else. Sophisticated gangsterism with good PR.

Years later, when I moved to New York City, I was shocked and hurt that no one on the other side of the Atlantic seemed to know or care about the divided and violent history of where I came from. But when I learned that British and even Southern Irish ex-patriots in New York were also broadly ignorant about our current status, I reached a new level of frustration. We were killing each other to be part of either a larger Irish or British identity, but outside the few hundred square miles of our province, no one seemed to care. What to take from that disheartening message?

Not much—until I started reading about astronauts.

I was researching for my book Here We Are, and I immediately recognized the way they described looking at the Earth from space was the same as how I’d been talking about Northern Ireland from across the distance of the Atlantic Ocean.

The summer after my son was born, there was growing violence building back in Belfast. As I watched news footage coming from across the ocean and saw that, like when I was growing up, it was kids who were hijacking and burning buses, throwing petrol bombs, rioting with each other and with the police, I wondered what these teenagers truly knew of the 800-year-old conflict. The reality is they probably didn’t know much. They’d simply inherited a story from their parents that was validated by their peers. They’d been told who to hate. This, I told myself, was not the story I was going to tell my son of where he came from. And as an artist, it was perhaps my biggest epiphany—that the most powerful thing we can do as civilized human beings is change the story. We can always, always, change the story.

- Oliver Jeffers