208. Sad Songs and Waltzes – Carmen Radley

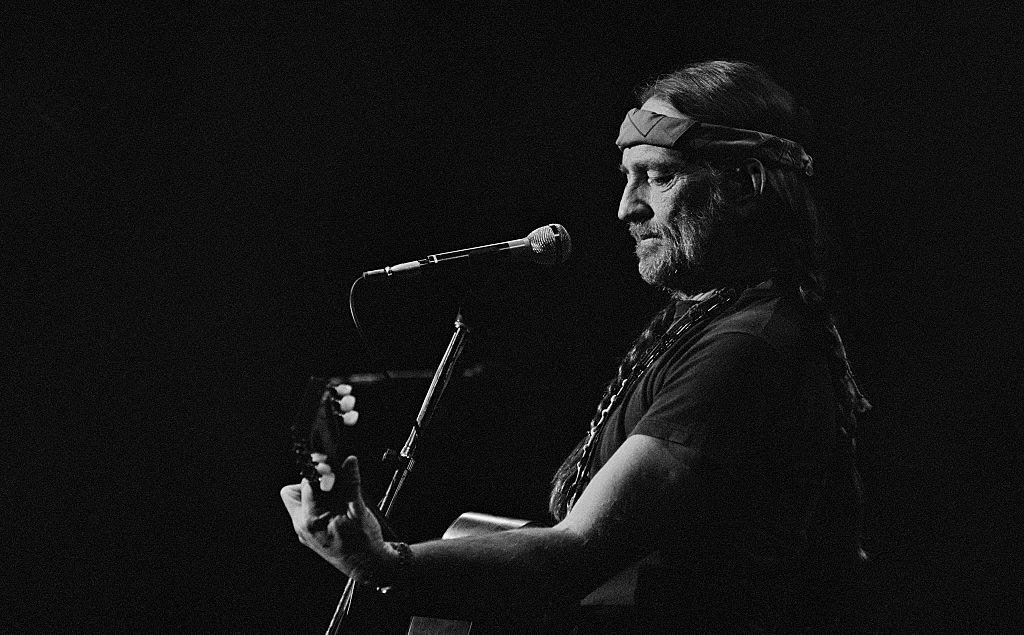

Image by Jay Dickman via Getty Images

When we hear tales of woe set to minor chords, even if we know cognitively that nothing’s wrong, we can’t help but be fooled into feeling it. Then when we cry, our bodies release the hormone prolactin, which has a soothing effect.

I’m going to talk about sad songs, but first I’m going to talk about the legendary Texas singer and songwriter Willie Nelson. I was born and raised in Texas and grew up hearing his greatest hits and a fair bit of Willie lore, but back then, I wasn’t anything close to being a serious student of his music—or anyone else’s for that matter. In fact, one of the handful of albums I owned in high school was Cake’s Fashion Nugget, and one of my favorite tracks was a song called “Sad Songs and Waltzes.” Until about a month ago, I had no idea it was a Willie cover.

But recently I began listening to a podcast called One by Willie, where John Spong of Texas Monthly magazine talks to notable Willie Nelson fans about one of his songs they really love. I spent two weeks in New York in August, and while I was there there, I listened to every episode and every album mentioned too. As I meandered the city streets, I felt melancholy and wistful, partly a longing for home, partly a response to the songs themselves. Yet I wasn’t actually sad. Quite the opposite: After even the saddest songs, I felt somehow expanded and open and connected to the wider world.

It was something that more than one guest on the podcast mentioned—for example, Charley Crockett said it of “Face of a Fighter,” which uses a boxing match as a metaphor for having your heart broken. As the steel guitar whines mournfully, Willie sings, “These lines in my face caused from worry/ Grow deeper as you walk out of sight./ Mine is the face of a fighter/ But my heart has just lost the fight.” It’s such a sad song, Crockett says, but it’s somehow comforting—and I agreed with him. At the end, I felt like I’d been sitting with a friend, commiserating over heartache, feeling less alone.

Of course, this isn’t limited to Willie Nelson’s music. The paradox of sad songs making you feel good is so well known that if you type the words “why do sad songs” into a Google search bar, it autofills with phrases like “make me happy” and “make me feel better.” Musicologists have developed a range of theories about this, including brain chemistry and evolutionary advantage. The musicologist David Huron argues that since the human auditory system is primed toward hypervigilance as a means of survival, this spills over into music. We listen on a knife’s edge, working to identify patterns and deviations, making meaning from abstract sounds as a way to protect ourselves. When we hear tales of woe set to minor chords, even if we know cognitively that nothing’s wrong, we can’t help but be fooled into feeling it. Then when we cry, our bodies release the hormone prolactin, which has a soothing effect.

Explanations like these make logical sense to me, but they also seem so reductive, so flat. Maybe it’s human frailty for me to want my response to Willie’s “Too Sick to Pray”—a song that has me welling with tears now, just typing the title of it—to be more than brain chemistry or evolutionary destiny. Maybe it’s sentimental to want the sad song effect to speak to the human capacity for empathy and compassion and connection, to want it to point toward something divine in humanity.

But that is what I want it to be. I want it to mean that even when Willie is going through his absolute worst, I’d rather be with him than on my own.

– Carmen Radley